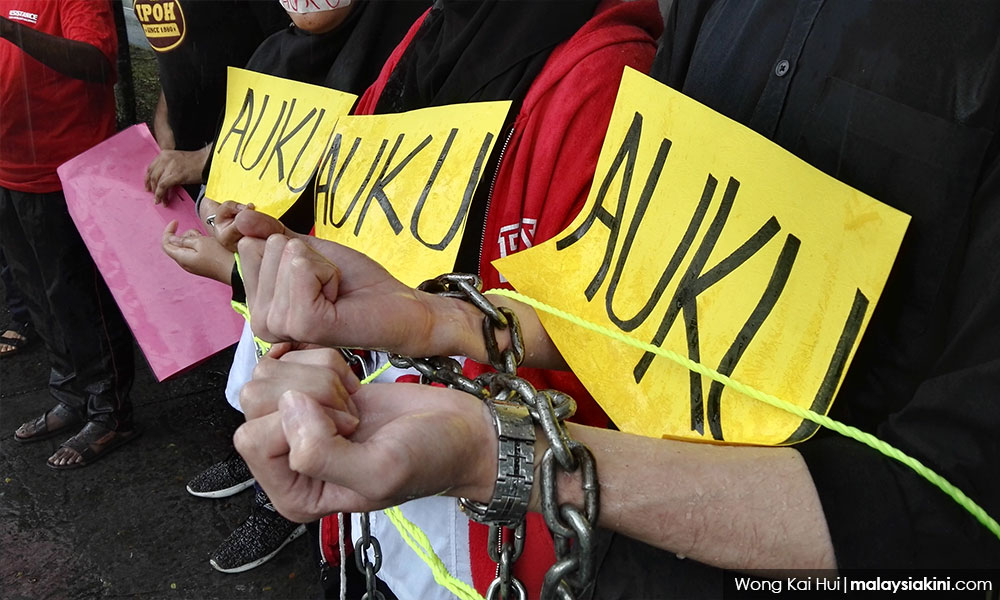

When will our varsities be free of Auku?

When will our varsities be free of Auku?

COMMENT | Earlier this week, our Education Minister Maszlee Malik announced that he would propose abolishing controversial restrictions on the rights of university students during the next Parliament sitting and he committed to ensure all politically motivated charges against university students would be dropped.

This would be a monumental reform for Malaysia, and it can’t come soon enough.

In June 2018, my organisation Fortify Rights published a 63-page report documenting the findings of a two-year investigation into the use of the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971 (Akta Universiti dan Kolej Universiti 1971 or Auku) to restrict the rights of university students in violation of international human rights law.

We documented how the former BN government misused Auku and its by-regulations to constrain and influence university students to prevent them from engaging in political life and discourse and to restrict their rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.

As long as these provisions continue to exist, basic freedoms are under threat and these threats have consequences that extend beyond the university campus.

For instance, on July 31, the head of the Safety and Security Department at the Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) threatened disciplinary action against three students who criticised the university on social media for its silence following an alleged attempted rape of a female student by a UMS security officer on July 15.

The criminal trial against the suspect is still ongoing at the Kota Kinabalu Sessions Court.

Moreover, on September 7, Asheeq Ali (below, left) and Siti Nur Izzah were arrested under section 477 of the Penal Code for “trespassing” over a sit-in protest in front of the Putrajaya Ministry of Education Building and on September 16, eight student activists were arrested over a Malaysia Day rally in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah.

The previous government used Auku as a political tool. Favoured political appointees who sat as vice-chancellors in universities took cues from ministers and law enforcement authorities to initiate questionable disciplinary proceedings against students who opposed or held a different political view than the government.

The Pakatan Harapan government must prevent these patterns from continuing and they should act fast.

Before taking power, the Harapan coalition recognised the urgent need to reform Malaysia’s systems of higher education and to reinstitute the autonomy and independence of its students.

'People have grown up'

Promise 28 in its Buku Harapan Manifesto specifically promised that “(Auku) will be revoked because it is often times abused to suppress freedom of students,” and the Harapan coalition committed to “support a creative young generation that is free from oppression.” The Harapan government actually mentioned repealing the law three times in the manifesto.

“By now, the people have grown up,” said Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad. “They have understood. I think we no longer need this act.” In the dawn of Malaysia Baru - the new Malaysia - Maszlee and Foreign Affairs Minister Saifuddin Abdullah made similar remarks that Auku’s time had come.

Despite promises contained within the Harapan manifesto to abolish Auku and reform the higher education system in Malaysia - promises intended to be fulfilled within 100 days of the new government’s formation - moves to amend Auku remain slow and minimal.

On August 1, the Deputy Minister of Education Teo Nie Ching announced a five-year deadline to abolish Auku citing the need for more time to abolish and replace the act with a new law. With that, the attempt to silence student voices and diminish student activism echoes on.

There is no legitimate justification to institute a five-year reform period; particularly considering that elections will take place before such a reform schedule could be completed.

Furthermore, a 12-member committee set up by the Ministry of Education to review Auku and oversee the reform agenda lacks student representation. Without student involvement, reforms are more likely to miss the mark.

The promise to reform Auku was made by the Harapan government and reaffirmed this week by the Education Minister. The Harapan government should keep its promise.

The time is ripe for a catharsis of Auku’s shackle over students.

If the Harapan government is sincere in accomplishing the ideals of the rights-respecting democracy that its leaders lauded during the elections’ campaign, amending Auku and restoring basic freedoms for students is one of the many nation-rebuilding efforts that ought not to be delayed.

HENRY KOH is a human rights specialist with Fortify Rights and the author of the report mentioned above. Follow him on Twitter @HenryKoh45.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/446047

Comments